How Finland won the war against homelessness (mostly)

Finland has all but won the war on homelessness thanks largely to its focus on providing long-term solutions, rather than temporary ones.

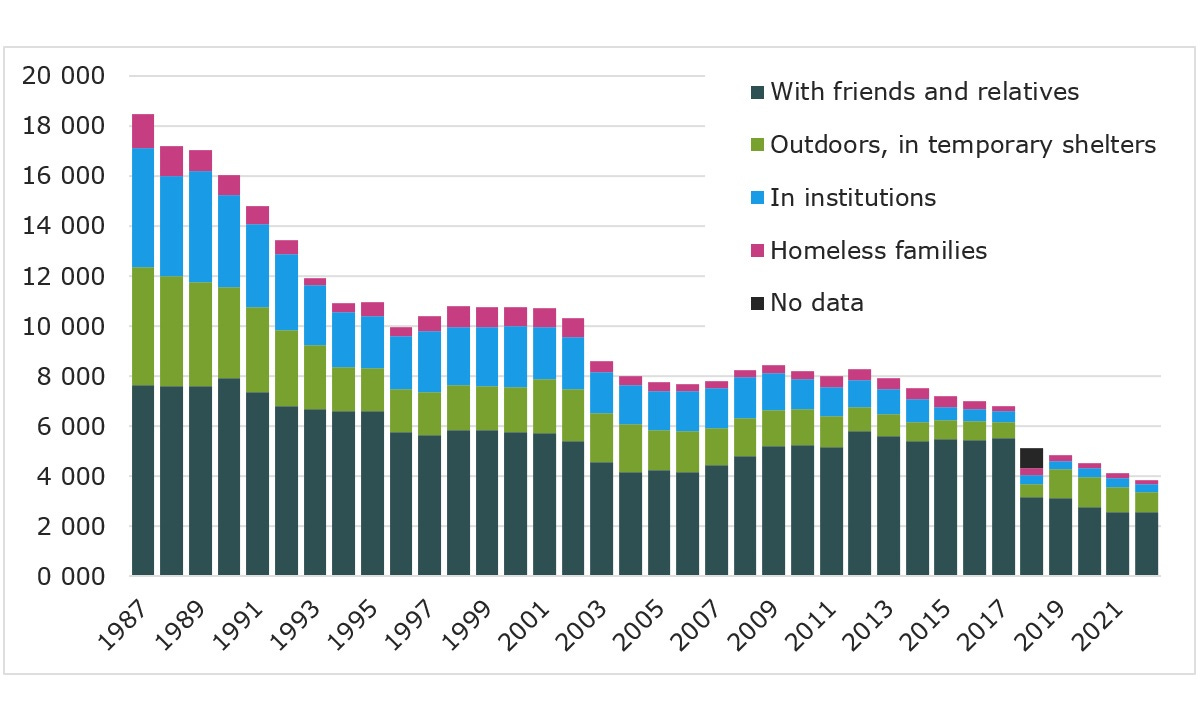

Despite its growing population, the number of homeless people in Finland has fallen from over 18,000 in 1987 to around 8,500 in 2009, and only 3,686 in 2022 — or just 0.07% of the population.

That figure is even more impressive when considering that Finland uses a broad definition of homelessness that includes people who are temporarily living with friends and relatives. In fact, 70% of its homeless population fit into that category.

At the end of 2022, only 479 people were living outside, in stairways or in the nation’s last-remaining overnight shelters, according to data from the Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (ARA).

By 2020, “practically no-one was sleeping rough on a given night in Finland”, according to a report by economists at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

“Finland’s success is not a matter of luck or the outcome of quick fixes,” the authors write. “Rather, it is the result of a sustained, well-resourced national strategy, driven by a ‘housing first’ approach, which provides people experiencing homelessness with immediate, independent, permanent housing, rather than temporary accommodation.”

An analysis of the policy, published in Oxford Academic, highlights the fact that homeless people can go straight to living in a rental apartment, with no temporary arrangements in between, and no preconditions. They’re then offered assistance with health and social problems, such as substance abuse.

The idea, according to the architects of the policy, is that “a person does not have to first change their life around in order to earn the basic right to housing. Instead, housing is the prerequisite that allows other problems to be solved.”

Here’s how Finland made it work:

First, the government focused on converting shared shelter facilities into private apartments for formerly homeless people. This mostly closed the chapter on short-term solutions and expanded the supply of housing.

At least 25% of new urban homes built by private developers must be affordable, social housing stock. This policy has further boosted the supply of apartments, and some of those units are acquired or leased for the homeless.

While these measures require upfront funding, officials say the costs are more than offset by the associated reduction in spending on shelter, healthcare and law enforcement.

Yes, but: The analysis published in Oxford Academic notes that Finland didn’t have a substantial homelessness problem to begin with, at least relative to most other countries.

The authors also note that while it was a government-led policy, big cities and non-governmental organisations played a major role in making it work.

Nevertheless, Finland’s success adds credence to the theory that short-term solutions end up costing governments more.

A recent Canadian study found that once-off cash transfers to homeless individuals, to help them secure apartments and other basic necessities, ended up paying for themselves.